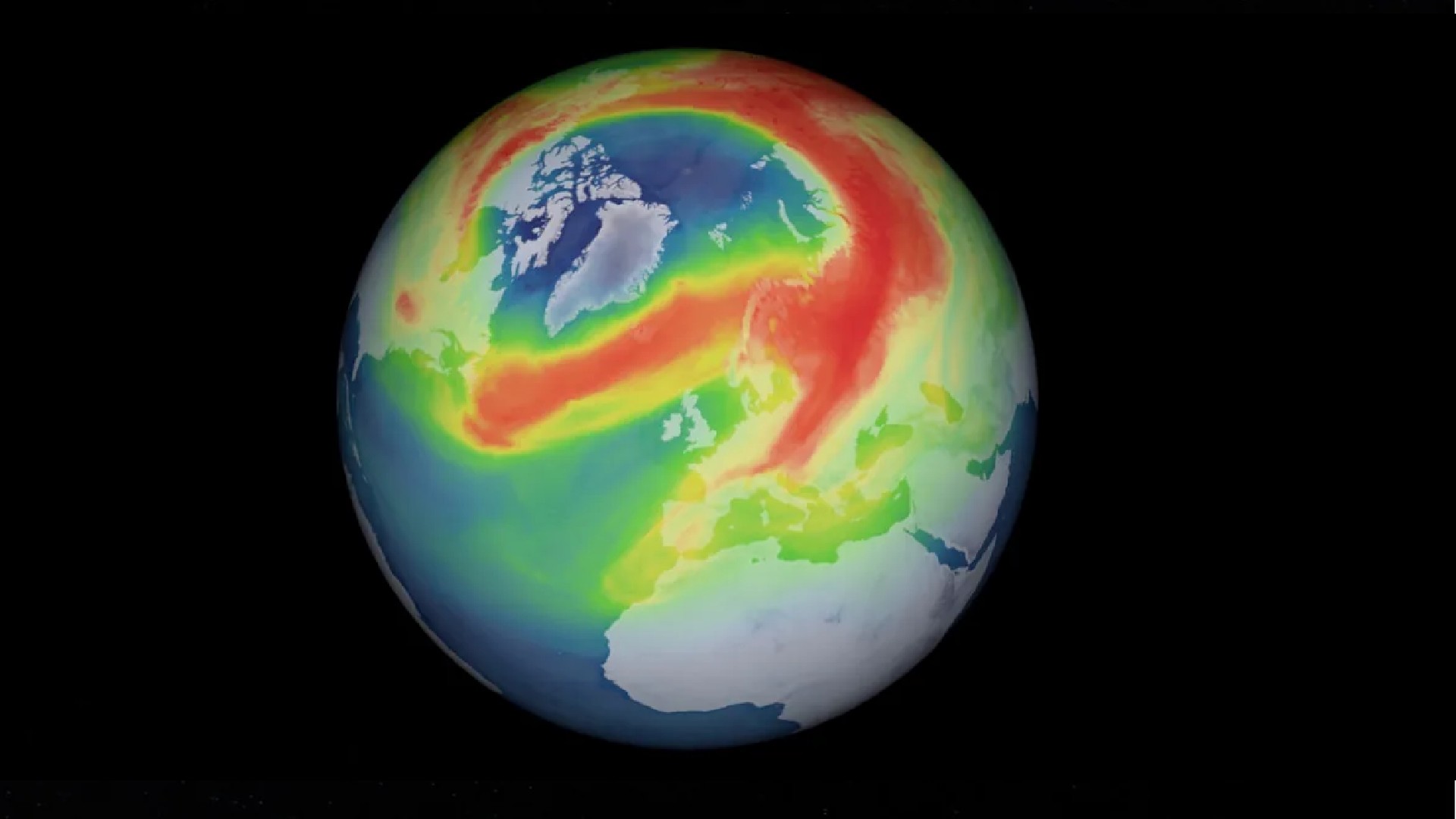

Early last year, a huge hole opened up in the ozone layer over the Arctic, encompassing an area of up to 1 million square km, albeit smaller than the Antarctic ozone hole, which is roughly around 20 to 25 million square kilometers in size.

Although the hole closed by springtime, two months after opening up, it left scientists puzzled about the cause behind it.

A new analysis performed by scientists from the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science at Peking University points to record-breaking temperatures in the North Pacific Ocean during winter as the cause behind the unusual occurrence. The analysis published in the journal Advances of Atmospheric Sciences suggests high chances of it being a regular occurrence in the future.

The researchers ran a series of simulations using satellite data and found high sea surface temperatures during winter in the North Pacific Ocean caused lowered Arctic westerly winds.

These winds blow through the region throughout winter up until spring and can trigger polar cloud formation if their temperatures are cold enough for long periods.

Cloud formation in the stratosphere in the North and South poles plays a key role in severely depletion ozone. Unlike over the Antarctic, the stratospheric vortex in the Arctic is usually too warm for polar stratospheric cloud formation.

The researcher found that during February and March 2020, North Pacific ocean surface temperatures reduced planetary wave activity, which in turn caused frigid and persistent stratospheric polar vortex during the same period.

According to Prof. Yongyun Hu, lead author of the study, the record Arctic ozone loss in spring last year indicates that substances that deplete ozone in present-day are still sufficient to cause springtime depletion. The results of the analysis suggest that ozone loss is most likely to be a recurring phenomenon.