Over the last several decades, astronomers have discovered approximately 5,000 different exoplanets, planets that are not from our own solar system. However, they have all come from our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

Astronomers have discovered the first exoplanet that originates neither from our solar system nor our galaxy, but rather from the spiral galaxy Messier 51 (M51), sometimes called the Whirlpool Galaxy due to its distinctive appearance.

It is difficult to locate exoplanets in deep space, especially from other galaxies. Nearly all of the other exoplanets discovered so far have been less than 3000 light-years away from Earth. In contrast, the new planet in M51 is approximately 28 million light-years away.

The study results, which directed to discovering the exoplanet, were announced in a new paper in the journal Nature Astronomy. Researchers from the Center for Astrophysics of the Harvard & Smithsonian in Cambridge (CfA), Massachusetts, accompanied the study using NASA’s powerful 22-year-old Chandra X-ray observatory.

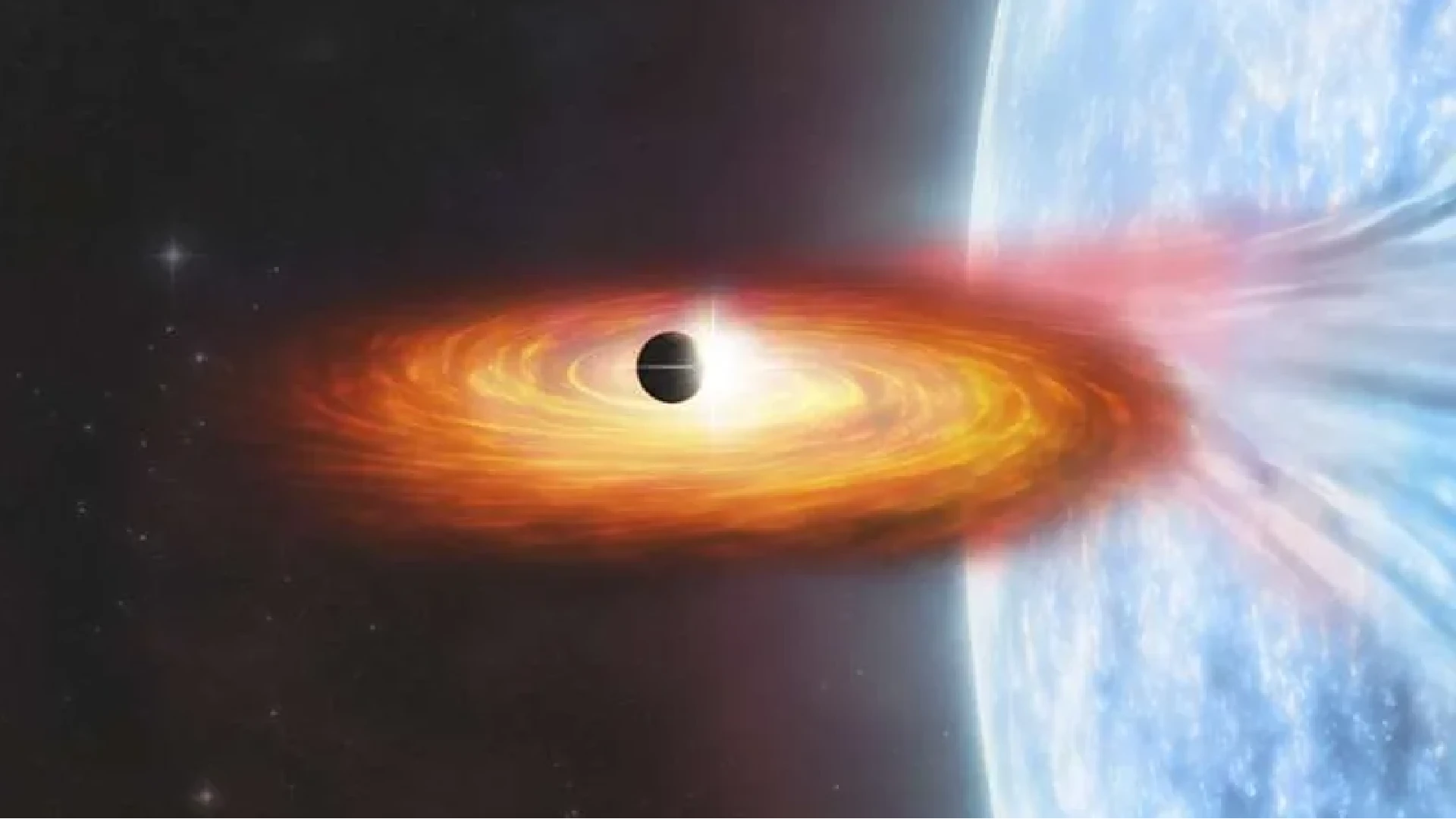

The exoplanet is located within the spiral galaxy Messier 51. Image courtesy of Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

The exoplanet is located within the spiral galaxy Messier 51. Image courtesy of Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

In a statement, Rosanne Di Stefano, lead author of the study and an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics at the Harvard & Smithsonian in Cambridge (CfA).

“We are working to open up a whole new arena for obtaining other worlds by searching for planet candidates at X-ray wavelengths, a strategy that makes it possible to discover them in other galaxies,”

Harvard researchers used the same method used to detect thousands of other exoplanets, called transits. As a planet passes in front of its star during its orbit, the brightness of the star dips, allowing astronomers to detect it.

To confirm their observation, researchers will have to wait for the planet to pass in front of the star again due to the inherent flaw in the technique. Given the distance between Earth and the planet, that could take a long time.

“To verify that we’re observing a planet, we would probably have to wait decades to see another transit,” Nia Imara, co-author, and researcher from the University of California at Santa Cruz, said in a statement. “And because of the ambiguity about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn’t know exactly when to look.”