For 35 years, Northwestern University astronomy professor Farhad Yusef-Zadeh has been studying mysterious cosmic ray electron strands spanning up to 150 light years across the Milky Way’s center.

Yusef-Zadeh was able to find ten times more strands with the help of his team – which is impressive since we don’t know what they are made of or where they came from.

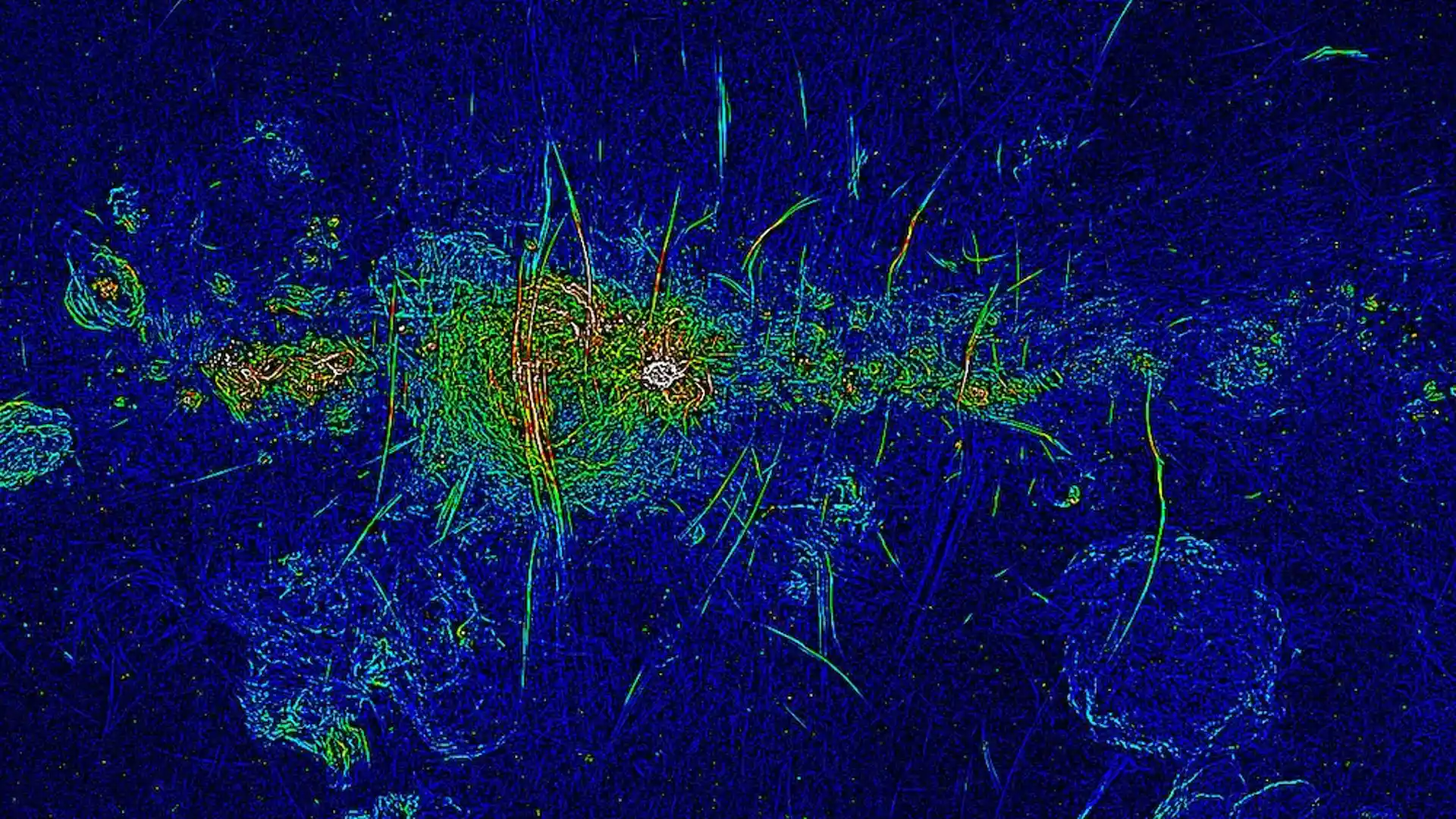

Using the MeerKAT telescope at the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory, the team was able to view almost 1,000 of these mysterious filaments, as detailed in a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“We have studied individual filaments for a long time with a myopic view,” Yusef-Zadeh said in a statement. “Now, we finally see the big picture — a panoramic view filled with an abundance of filaments.”

In the course of his career-long investigation, it’s a significant moment.

Just looking at a few filaments makes it challenging to draw conclusions about what they are and how they got there, he said. “This is a watershed moment in furthering our understanding of these structures.”

The panorama was created by stitching together 20 separate observations made by the MeerKAT observatory over 200 hours. According to Yusef-Zadeh, the resulting image is awe-inspiring and “like modern art,” according to Yusef-Zadeh.

Credit: Northwestern University/SAORO/Oxford University

Although many questions are left unanswered, the team is willing to make some educated guesses.

Variations in the radiation emitted by the filaments, for instance, suggest they are not the leftovers of supernovae but rather are evidence of past activity of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy.

“This is the first time we have been able to study the statistical characteristics of filaments,” Yusef-Zadeh said in a statement. Using magnetic fields as an example, the team found that the magnetic field intensifies along the strands.

Their distances from each other are also the same.

“We still don’t know why they come in clusters or understand how they separate, and we don’t know how these regular spacings happen,” Yusef-Zadeh said.

But getting a complete understanding will require “more observations and theoretical analyses,” he added, a process that “takes time.”

“Every time we answer one question, multiple other questions arise,” he added.